Her Impact: The Cheetah Girls (2003)

a crash course in Black + Brown girl Bildungsroman and spectatorship

In 2003, one of the most prominent media institutions behind Americana controlling imagery put their backing behind a young adult book series adaptation about girls of color, their bonds, and their dreams. The resulting film became one of the most commercially successful projects in the then-young network’s history, demonstrating the resonant appeal of Black femme Bildungsroman. The Cheetah Girls (dir. Oz Scott, 2003) was the first musical-movie in what became a three-film trilogy that continues to be celebrated nearly twenty years later.

Drawing from Deborah Gregory’s source text, the film establishes a thread in the cosmology of Black girlhood aesthetics told through the story of an aspiring teen girl group. The film’s initial popularly on the Disney Channel cable TV vertical was buttressed by an affiliated soundtrack and real-life musical rollout featuring associated costuming, tours, and merchandise. These methods of story-continuation established the eponymous group as a legitimate act targeted for tween girls of color, offering them both fictive and material avenue for subcultural production. Though developed through the heavy marketing tactics of a disproportionately powerful media conglomerate, the sentimental impact of this specific take on girls’ kinship cinema remains necessary in the larger canon of cinematic femme narrative.

One of the defining traits of Black girl cinema is its challenging of the assumption that Black and Brown girls are not active consumers of and participants in cinema. I use “girls” here deliberately, to draw particular attention to the intersection of ageism in the existing discourse surrounding race and gender-reflexive cinema.

During the 80s, 90s and early-2000s waves of American teen movies, girls of color were active consumers of popular coming-of-age movies, including many white girl bildungsroman films which spoke to some shared experiences that all girls relate to—chief among them, 1) the bonds between girls and 2) maternal-daughter dynamics.

Dispelling the notion that Black girl coming-of-age stories don’t sell

Disney™ is the world’s largest multinational entertainment company in terms of revenue. Their market share encompasses a third of the global television and movie industry. In its thirty-six-year history, Disney Channel—a family-oriented cable service first founded in 1983 and flagship property of Disney’s direct-to-consumer business segment— owing their success in so small part to several projects centering characters and storylines of Black girlhood.

Two projects in particular come to mind: Disney Channel Original Movie, The Cheetah Girls (2003) and Disney Channel Original Series, That’s So Raven (2003-2007). Respectively, they were the first made-for-TV movie musical in Disney Channel's history with a worldwide audience of over 84 million viewers, and the highest-rated program on the network, as well as the first series in the network's history to produce at least 100 episodes. Both also stared tenured child actor Raven-Symoné.

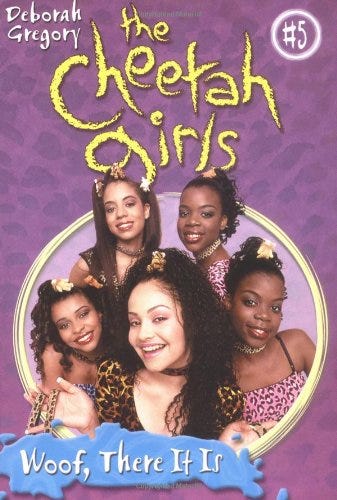

In the case of both programs, commercial and critical acclaim were so great that they inspired two spin-off series and affiliated soundtracks including two RIAA certified Platinum albums. The profitability across works speaks also to the reach of Black female auteurship as the film was a made-for-TV adaptation of a 16-book young adult novel series by Deborah Gregory.

The book series, published from 1999 to 2014, follows a female vocal group seeking success and fortune while going the trials of teenage adolescence in the fictional “Jiggy Jungle.” The backdrop, its characters, were all envisioned as people of color, a setting existing almost outside of a white gaze.

Not unlike James Baldwin’s allegorical Beale Street, a real street located in Memphis, Tennessee, the Cheetah Girls books use unspecified location to build out a poetic depiction of Black life. In 2018’s breakout feature and major awards contender “If Beale Street Could Talk,” Oscar-winning “Moonlight” director Barry Jenkins sets his Beale Street in early 70s Harlem. His directorial interpretation externalizes a deeply symbolic site Black love and resilience into an existing site of the same motifs in Black history and contemporary life. I would charge that Deborah Gregory achieves the nuanced symbolism with the ‘Jiggy Jungle,’ which like “Beale Street” is set in New York City in its film adaptation.

As is the case with many movie adaptations of books, creative license was taken with certain details. In the books there are five Cheetah Girls, but in the first film adaption and its sequel, The Cheetah Girls 2, there are only four. In the third installment, there are only three. However, the most crucial characteristics of Gregory’s original Cheetah Girls were honored, most notably the intersectional ethnic backgrounds of her Black female characters.

In the books, all primary characters are girls of color. Their race and ethnic backgrounds are drivers of their shared experiences in the fictional-NYC’s Jiggy Jungle, centering kinship and adolescence, not trauma.

The Cheetah Girls films were also notably successful in terms of merchandising and sales for its concert tour and soundtrack albums. The first film in 2003 was the first made-for-TV movie musical in Disney Channel's history had a worldwide audience of over 84 million viewers. The second movie “The Cheetah Girls 2” (2006) was the most successful of the series, bringing in 8.1 million viewers in the U.S. An 86-date concert tour featuring the group was ranked as one of the top 10 concert tours of 2006; the tour broke a record at the Houston Rodeo p set by Elvis Presley in 1973, selling out with 73,500 tickets sold in three minutes.

Still, though, even a heavily-funded dollar Disney Channel Movie™ cannot portray the totality of Black female adolescence, nor does it have an incentive to beyond its projected profitability. Although the network has achieved some feats of representation with characters like Raven Baxter (That’s So Raven), The Cheetah Girls and token Black female characters throughout its catalog of original first-run television series, there remain more nuanced, nonhegemonic stories of Black female femininity, identity, childhood, adolescence, and socialization to be told.

Contrasting with the hyper-capitalist media conglomerates that control the vast majority of not only American but worldwide televised programming, there are alternative spaces for visual narrative production that although have comparatively less funding and visibility experience greater freedom in expression.

It is here, in the margins of filmmaking and TV-production, that lesser represented experiences can come to life and although they may not experience the more immediate success of larger media giants’ projects, are just as desired and even more socio-politically pertinent.

While The Cheetah Girls and That's So Raven come to mind, Disney also had Twitches (although the Mowry twins are biracial), The Proud Family (and it's movie), as well as Zapped (although Zendaya is also biracial), KC Undercover (again with Zendaya but here both her characters' parents are Black) and The Color of Friendship. It's not much but it's sum'n. Anyway, good post. I enjoyed reading it🖤