Sharp Edges, Soft Rebellion: The Black Woman Dandy

On the Quiet Noise of Suits, both Tailored and Exaggerated

The women’s power suit, so often described in 1980s shorthand—pinstripes, shoulder pads, “career wear”—owes its fundamental structure not to Reagan-era boardrooms, but to the rebellions of midcentury youth and prior moments of self-announcement through sartorial insubordination. Worn by swing dancers, jazz musicians, and pachucos alike, the zoot suit’s exaggerated silhouette—a long drape coat, ballooned trousers, wide lapels—signaled defiance against wartime austerity and racialized policing, anticipating the ethos of contemporary female dandyism: to claim space unapologetically, to be seen on one’s own terms. Monica L. Miller writes in Slaves to Fashion that “Black dandyism reveals the tension between being seen and being surveilled” (Miller 23). For Black women, this tension is doubled. To dress up has never simply been to adorn—it is to enter the archive and re-edit it.

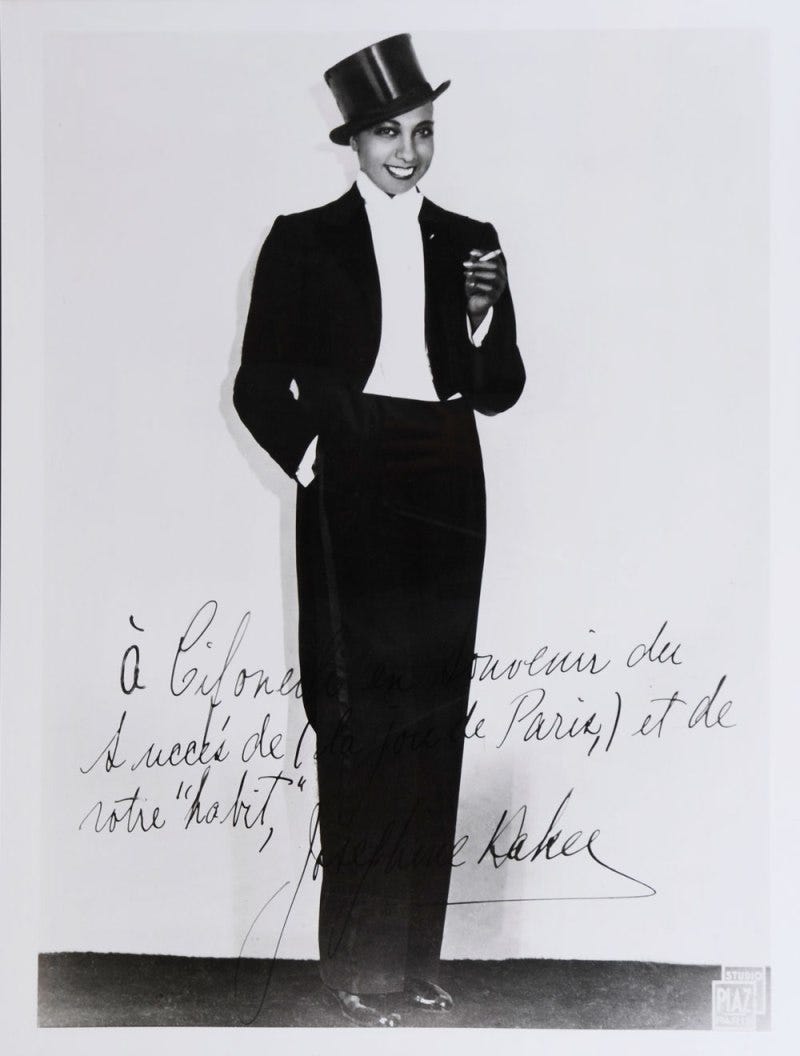

The Black female dandy—with her impeccable tailoring, strategic accessorizing, and calculated presentation—engages in what Miller describes as the practice of using “immaculate clothing, arch wit, and pointed gesture to announce their often controversial presence.” These become tools of the self-making process. This carries particular significance for Black women, whose bodies have historically been sites of appropriation, regulation, and exploitation. By adopting and adapting elements traditionally associated with male dandyism—pocket squares, suspenders, watch chains, immaculate shirting—these women craft identities that refuse the limitations of both racialized and gendered expectations.

Janelle Monáe, with her years-long commitment to black-and-white suiting, is often read as androgynous, but in her styling, the tuxedo takes on a larger manifesto on gender, self-presentation, and power. “The uniform kept me honest,” Monáe once said. “It kept me humble. It made me remember the working-class people who I came from.” It is significant that a woman who sings about androids and memory would choose a historically fraught garment to anchor her identity. The suit, in her hands, becomes both armor and invitation.

The cultural memory of tailored clothing and its links to dignity, danger, and class aspiration is not lost on the current generation of Black women who wear suits not for necessity, but for sport. Teyana Taylor at the 2023 Met Gala arrived in a chopped, deconstructed Thom Browne ensemble that married Victorian severity with Harlem Renaissance cool. Her fashioning “a neo-refitting of historical resistance dress.”

Where the zoot suit’s voluminous shoulders, high-waisted trousers, and dramatic silhouettes once announced the presence of marginalized men in urban spaces, today’s tailored women’s suits perform similar cultural work on Black women’s bodies, demanding visibility in environments constructed to render them invisible.

This practice of self-fashioning—of dressing with historical consciousness—is a throughline in the work of Dr. Jonathan M. Square, who describes fashion in the Black diaspora as “an embodied archive” (Square). His collective, Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom, places sartorial choices in direct conversation with resistance. Clothes do not merely decorate—they document.

Shelby Ivey Christie, the fashion historian who has built a digital canon one thread at a time, writes often about the politics of dress, especially when it comes to Black women and luxury. “Style is our first language,” Christie tweeted in 2021. “Before we speak, we show.”

“Throughout history,” notes Dr. Jonathan M. Square, founder of the Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom collective, “Black people have used clothing not merely as protection or adornment, but as a critical technology of selfhood that allows for the articulation of identity under conditions designed to deny such possibilities.” When a Black woman selects a custom suit over conventional feminine attire, when she positions a boutonnière on her lapel or adjusts her tie with precision, she participates in this tradition of fashioning selfhood against erasure.

The contexts in which these sartorial choices appear amplify their significance. In corporate environments, the Black female dandy’s presence disrupts assumptions about professionalism that have long been coded as both white and male. In artistic spaces, her tailored silhouette references a complex history of gender performance and racial resistance. Even in casual settings, her deliberate styling signals what Janell Hobson terms “a literacy of self-presentation that acknowledges historical consciousness while refusing historical determinism” (Hobson).

What distinguishes the contemporary Black female dandy from both her male predecessors and white female counterparts is her navigation of multiply marginalized identities through deliberate aesthetic choices. Her dandyism operates as both shield and statement—protecting against misreading while simultaneously asserting presence. The precise cut of her trousers, the strategic placement of cufflinks, the calculated tilt of a fedora—these elements compose not merely an outfit but a visual argument about belonging, authority, and self-determination.

As Christie observes, “When Black women adopt tailored clothing historically associated with masculine power, they aren’t simply borrowing from men’s closets—they’re reconfiguring the very language of fashion to speak to their specific experiences of race and gender.” This reconfiguration matters because fashion, particularly for Black subjects, has never been trivial but rather what Miller calls “a critical site for the negotiation of race, class, sexuality, and gender” (Miller 9).

The Black female dandy’s emergence represents not merely a trend but a theoretical intervention—a dressed body that challenges fundamental assumptions about who can occupy certain aesthetic territories and what those occupations signify. In the careful selection of a pocket square, in the perfect dimple of a tie knot, in the deliberate shine of oxfords, these women continue a tradition of using style as both a survival strategy and a self-announcing act.

ur writing is beautiful 🩷🩷🐞genuinely <33 wld love if u cld see what u think about my recent one eeee i haven’t written in a while but wld love feedback😭❣️❣️✨